On the British Geological Survey’s map, chalk is represented by a swathe of pale, limey inexperienced that begins on the east coast of Yorkshire and curves in a sinuous inexperienced sweep down the east coast, breaking off the place the Wash nibbles inland. Within the south, the chalk centres on Salisbury Plain, radiating out in 4 nice ridges: heading west, the Dorset Downs; heading east, the North Downs, the South Downs and the Chilterns.

Stand on Oxford Avenue in the course of the West Finish of London and beneath you, beneath the concrete and the London clay and the sands and gravels, is an immense block of white chalk mendacity there within the darkness like some huge subterranean iceberg, in locations 200 metres thick. The Chalk Escarpment, as this block is understood, is the one largest geological characteristic in Britain. The place I grew up, in a suburb of Croydon on the fringe of south London, this chalk rises up from beneath the clays and gravels to kind the ridge of hills known as the North Downs. These add drama to quiet streets of bungalows and interwar semis: sometimes a spot between the homes exhibits land falling away, sky opening up, the towers and lights of the town seen far within the distance.

The British Geological Survey (BGS) was established (because the Ordnance Geological Survey) in 1835. The world’s first nationwide geological survey, its authentic remit was to survey the nation and produce a sequence of geological maps. As we speak, the BGS, which nonetheless produces the “official” map of the UK’s geology, is greatest described as a quasi-governmental organisation cut up between analysis, industrial initiatives and “public good”. Numerous its work is now achieved outdoors Britain: on the time of writing, initiatives embrace research of groundwater within the Philippines and volcanic exercise within the Afar area of Ethiopia.

One week in early October, 4 members of the BGS arrange camp in a self-catering cottage close to the city of Tring within the Chiltern Hills, about midway between London and Oxford. They had been on a coaching train as a part of a undertaking to supply a brand new geological map of the chalk of southern England. On the day I arrived, the picket desk in the primary room was coated with maps, books, a half-drunk bottle of pink wine and a packet of chocolate digestives. Discipline chief Andrew Farrant, tall and skinny, with steel-rimmed glasses, was consuming a cup of tea. He had a type of leather-based holster connected to his trousers, from which swung a geological hammer with a surprisingly wicked-looking lengthy, pointed finish.

The Seven Sisters cliffs in East Sussex, England. {Photograph}: eye35.pix/Alamy

Farrant has been engaged on the chalk-mapping undertaking on and off since 1996. “I’d say that not sufficient consideration is paid by the educational analysis neighborhood to understanding the geology of the UK,” he stated. “If I used to be doing this [mapping project] in east Greenland, then I’d in all probability get funding for it – east Greenland is attractive. And folks are likely to suppose that as a result of now we have a geological map of the UK, it’s all been achieved, however truly you’ll be able to nonetheless enhance it.”

The geology of the Chilterns, for instance, was final mapped in 1912. Since then, the self-discipline has modified fairly a bit. Geologists now find out about plate tectonics and radiometric relationship. There are laser-based distance measurements for elevation maps and digital terrain fashions and higher-definition Ordnance Survey maps, permitting hitherto unrecognised options to be recorded. All of this may have an effect on the maps which are produced.

And relating to the chalk, these new maps matter in a manner they didn’t in 1912, as a result of since then, the inhabitants of the south-east has elevated by roughly a 3rd. Specifically, this leap has put stress on the area’s transport programs – usually created by tunnelling although chalk to kind such initiatives as HS2, the Gravesend tunnel and Crossrail – and the area’s water assets, a lot of them saved within the chalk aquifer.

Think about stumbling, blindfolded, by an unknown panorama, uneven terrain underfoot, and huge, exhausting objects rearing out of nowhere. With out respectable mapping, that is primarily the scenario for a tunnelling engineer confronted with an immense block of chalk. “Obstructions are a really massive difficulty,” Mike Black, Transport for London’s principal geotechnical engineer, recalled in an interview in New Civil Engineering. “We spend an enormous period of time on desk research attempting to work out the place every thing is or the place it could be.”

An sudden flint band or exhausting rock stratum can shatter the defend of a £100m tunnel-boring machine. Hit a fracture or a seam of clay, and your tunnel – stuffed with males and machines – would possibly flood with water. The Channel tunnel, as an example, doesn’t go in a straight line from A to B, however follows as a lot as doable a single layer within the chalk that is among the most fitted for tunnelling. To plan the route, engineers checked out samples of chalk from boreholes and analysed the microfossils in an effort to discover the easiest way by. “That saved Eurotunnel in all probability half one million kilos,” Farrant informed me.

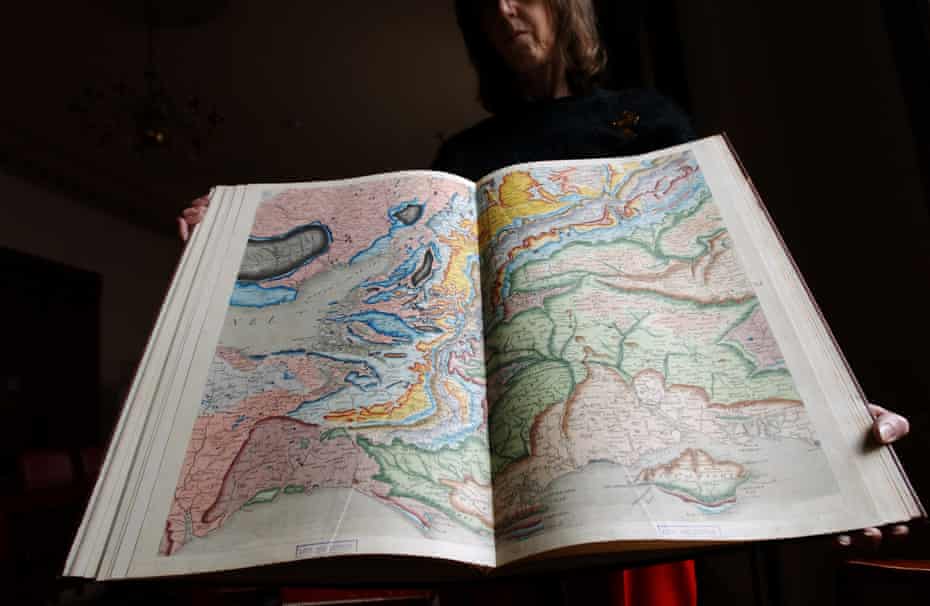

The world’s first true and complete geological map of a rustic – England, Wales and (most of) Scotland – was printed in 1815, by a surveyor named William Smith. In an age of gents geologists, Smith wasn’t wealthy, posh or well-connected – in actual fact, his social standing barred him from membership of the Geological Society of London – however he was obsessive about rocks, fossils and the thought of mapping the geology of Britain. He spent years travelling across the nation to collect materials, ultimately bankrupting himself whereas producing the primary copies of his map.

As we speak, one of many authentic copies hangs within the entrance corridor of the Geological Society’s headquarters in Piccadilly. If you pull again the blue velvet curtain defending it from the sunshine, one among first issues that strikes you is its magnificence. The UK is furrowed by a sequence of curving strains working downwards proper to left to achieve some extent round Taunton in Somerset. The nation is a marbled mass of forest inexperienced, caramel brown, bubblegum pink, wealthy purple and pale lavender.

Smith’s map, you’ll be able to inform at a look that the nation is older within the west and youthful within the east; that, roughly talking, when you start within the south-east and journey north-west as much as the Highlands of Scotland, you journey again in time – from the latest formations of East Anglia to the traditional metamorphic rocks of the Highlands. Smith gave every stratum a special color, based mostly loosely on the color of rock they indicated, and graded in order that the strongest color represents the bottom of the formation, lightening upwards.

One in all William Smith’s maps (the Delineation of Strata, 1815) on show on the Geological Society in Piccadilly, London. {Photograph}: David Levene/The Guardian

One in all William Smith’s maps (the Delineation of Strata, 1815) on show on the Geological Society in Piccadilly, London. {Photograph}: David Levene/The Guardian

The colors Smith selected are, roughly, these nonetheless employed by all stratigraphers immediately. They’re based mostly on the colors of the rocks themselves: yellow for the Triassic sandstone of Shropshire, shaped from sizzling, dry deserts; pale pink for Cambrian granites extruded from prehistoric volcanoes in what’s now Wales; blue for the coal-bearing Carboniferous rocks of the Midlands, when that area was a land of seething, glistening swamps; pale, yellowish inexperienced for the white chalk, as a result of white would have proven up badly towards the paper.

Smith’s map helped to form the financial and scientific improvement of Britain through the Industrial Revolution. It confirmed the place coal to energy the factories could be discovered. The place clays and rocks to construct the rising cities could be quarried. The place tin and lead and copper might be mined. The place a canal or railway line would possibly most simply be dug. His map represented a rise not simply in information, but in addition in wealth.

Smith is typically often called “the daddy of English geology”. In 2003, one among his authentic maps was bought for £55,000. In Piccadilly, the society that will as soon as have refused him membership shows his relics like these of a saint: an oil portray full with a lock of Smith’s white hair sealed into the body and two uncomfortable-looking picket chairs.

The examine of chalk is what is typically termed “tender rock” geology. Mushy rock specialists examine “sedimentary rocks comparable to sandstones and limestones, whereas their “exhausting rock” counterparts work on the powerful igneous and metamorphic rocks comparable to granites and slates. The classes aren’t good, however the jargon sticks. Rivalry generally ensues. I as soon as met a retired sedimentary geologist who argued that “tender rock males” are all the time the extra considerate. It got here, he mused, from excited about the formation of sedimentary rocks. One rock unit shaped from the quiet accretion of layers of sediment over many hundreds of thousands of years. The sluggish, sluggish formation of worlds. And what about exhausting rock geologists? I requested him. “Laborious rock males are all bastards,” he stated.

The chalk world started to come back into existence round 80-100 million years in the past, when the Earth was getting into a warming part. Seas rose quickly, and one third of the landmasses current immediately disappeared beneath the rising waves. Geologists name this era the Cretaceous, after creta, the Latin for “chalk”, and it’s the longest geological time interval on the stratigraphic chart: at 80 million years, it lasted far longer than the 65 million years which have elapsed because it ended.

In areas the place chalk is discovered immediately, the water was stuffed with billions of microscopic organisms known as coccoliths. After they died, their skeletons sank down by the clear water, in such amount that in locations the ocean would have turned a milky blue. On the ocean flooring the skeletons piled up, forming a tender ooze. Over time, this compacted and hardened – residing bones translated into white rock. The uniformity of the chalk – these large thicknesses of rock, some a mile in depth – is testomony to a steady, slowly drifting world the place, for hundreds of thousands of years, nothing a lot occurred.

Throughout the late Nineteenth century, geologists started additional refining the present rock models of sort and time. However comparatively little consideration was paid to chalk. Geologists felt there wasn’t a lot to say about it, and little financial crucial to check it in larger element. It had some use as a fertiliser and, later, in concrete, however it incorporates no coal, oil, valuable minerals or metals, and is usually too tender to be a constructing materials.

Chalks cliffs at Beachy Head in East Sussex. {Photograph}: Gary Yeowell/Getty Photographs

Chalks cliffs at Beachy Head in East Sussex. {Photograph}: Gary Yeowell/Getty Photographs

Even amongst that subsection of the inhabitants who get excited by a very good piece of rock, for years chalk was seen as pretty uninteresting. When Farrant began work on the BGS in 1996, he informed me: “I obtained dumped on the chalk and I assumed, ‘Oh God, how boring.’ It seems I used to be unsuitable.”

In Britain – or, extra precisely, the place that was to turn out to be Britain – the following massive factor to occur to the chalk occurred about 50 million years in the past, when the African plate crashed into Europe. The land buckled up, forming a sequence of ridges together with the Pyrenees and the Alps. In Britain, a sequence of low chalk hills started to emerge from the ocean. At first they had been capped with mud and sandstones, however erosion ultimately did its work and shaped the naked chalk scarps of the South and North Downs and the Chilterns.

As we speak within the south-east of the UK, a lot of the chalk has disappeared beneath sprawling cities and suburbs, however the place it hasn’t been constructed over it produces a panorama usually considered as quintessentially English. Clean, rolling hills coated with brief turf. Mild slopes and steep escarpments, dry valleys and lonely beech hangers. Seen from a distance, it appears to ebb and swell just like the ocean from which it as soon as emerged.

On postcards and tea towels, pictures of chalk landscapes carry out a selected model of Englishness. “Chalk has fairly a central place in England’s cultural historical past – the white cliffs of Dover and all that stuff,” Farrant stated. “And but most individuals know nothing about what it’s and the way it shaped.”

On the fringe of the nation, the chalk turns into dramatic, unsettling. Standing on the seaside at Cuckmere Haven in Sussex, you lookup on the towering whiteness and it appears for a second as if it’s falling in the direction of you out of the blue sky. The uncovered chalk has one thing chilly and otherworldly about it. To see such whiteness, such brightness, feels unnatural.

From the south coast, the chalk runs beneath the Channel and reappears as one other set of white cliffs, which the French name the Côte d’Albâtre (“Alabaster Coast”) and the English have a tendency to not discuss very a lot. These had been a lot painted by Monet, Pissarro and Renoir. Chalk, which the English usually appear to treat as peculiarly their very own, lies beneath a lot of northern France, and bits of Scandinavia, the Netherlands and Germany.

Chalk cliffs on the Cote d’Albatre, or Alabaster Coast, close to Etretat in France. {Photograph}: Prochasson Frederic/Alamy

Chalk cliffs on the Cote d’Albatre, or Alabaster Coast, close to Etretat in France. {Photograph}: Prochasson Frederic/Alamy

In 1993, Richard Selley, then a professor at Imperial Faculty London, had been excited about the similarities between the chalk panorama of the North Downs and the Champagne area in north-east France. His neighbour had been unsuccessfully attempting to farm sheep and pigs on his property within the North Downs. Selley recommended he strive glowing wine. That winery now produces near 1m bottles of wine a yr, about half of it glowing – which might, if made in north-eastern France, be known as champagne.

As Farrant stated: “The English Channel can be a minor factor. It’s the identical deposit principally, so there’s no Brexit with the chalk.”

The Chiltern Hills run for 46 miles from Goring-on-Thames in Oxfordshire north-west to Hitchin in Hertfordshire. At their highest level – Haddington Hill in Buckinghamshire – a stone monument marks the 267-metre summit. A lot of this panorama is farmland. There are small villages huddled deep within the dry valleys, historic market cities and the sides of suburbia. I joined Farrant and his BGS colleagues there on a heat day of blue skies and powerful, low autumn gentle. Farrant and I set off with a brand new recruit known as Romaine Graham, who had been engaged on the chalk for 2 weeks and had blood blisters on the palms of her fingers from wielding her hammer.

We adopted a observe between hedgerows stuffed with fats, pink rosehips and rambling outdated man’s beard. We climbed over a barbed-wire fence between two ploughed fields; the place there aren’t any footpaths, the surveyors depend on the goodwill of landowners for entry. Farmers are normally OK, however gamekeepers are usually territorial. By the sting of the sphere, Farrant and Graham used their hammers to interrupt open items of chalk. “That is the Zig Zag Chalk,” Farrant says. “It’s medium-hard, pale gray and blocky.”

We all know now that the chalk was by no means simply the three giant, monolithic blocks of rock (and time) that the Nineteenth-century geologists proposed – Decrease, Center and Higher. Within the Eighties, geologists started subdividing the chalk into 9 formations. As we walked, Farrant and Graham started to debate variations between formations. To the uninitiated, these can appear negligible. Working in chalk is all about getting your eye in, studying the subtlest of clues. The Zig Zag, for instance, they described as “quite uninteresting, John Main gray”. The Seaford, against this, is tender, clean and vibrant white, and infrequently incorporates giant flints. The Holywell is creamy white, stuffed with small fossils. The Lewes is white, creamy or yellowish. Chalk rock may be very exhausting, nearer to the exhausting limestones of Cheddar Gorge than the tender, crumbly white stuff that almost all of us consider as chalk. Every formation represents a special world, and every of those worlds existed for a lot, far longer than people have been on the planet.

Wright here there aren’t many outcrops, the surveyor should discover different methods of getting on the chalk. You search for outdated quarries and pits, badger setts, newly ploughed fields, and even graveyards, the place the earth has been just lately turned. Engaged on a web site at Stonehenge, Farrant discovered himself on his fingers and knees searching for molehills beside the roar of the A303. “Doing this work has obtained more durable just lately,” he stated. “Over the previous 10 years farmers stopped deep ploughing. Now they use one thing known as a no-plough technique, the place they only put the seeds straight within the floor, which is improbable for wildlife, however for us it’s a proper ache.”

Up forward he noticed a small copse, which he thought would possibly comprise the stays of an outdated chalk pit, and dived into the undergrowth. “We spend a variety of time preventing by bushes,” Graham stated. “Andy loves it.” By the point we caught up with him, he was sitting in the course of the undergrowth hacking at a chunk of chalk. “Totternhoe Stone,” he confirmed.

Mapping the chalk additionally depends closely on what Farrant calls “panorama literacy”: the power to find out what’s underground by learning the floor. Which may imply understanding that rounded hilltops are sometimes Seaford chalk, and flat fields sometimes Zig Zag. Or that the place chalk is on the floor you discover beech, yew and holly, and the place it’s deeper there are pine timber, heather and gorse.

By early afternoon the sunshine had modified, and the fields glowed lavender and apricot. Up shut the soil was gentle gray and dry, and the surveyors’ footprints regarded like they had been on the moon. The hill of Ivinghoe Beacon loomed above us – as soon as the positioning of a bronze-age barrow, then an iron-age fort – rising up abruptly from the Vale of Aylesbury to kind a part of the ridge of the Chilterns.

A fish fossil in a block of chalk discovered close to Dover. {Photograph}: Interfoto/Alamy

A fish fossil in a block of chalk discovered close to Dover. {Photograph}: Interfoto/Alamy

As we started to climb, we handed an uncovered financial institution of chalk, created when the trail was lower into the hillside. Right here the surveyors thought they may discover fossils. Graham lent me her hammer, and after 5 minutes we’d amassed a small assortment of long-dead sea creatures. Items of chalk cut up in half to disclose a brown tubular worm, a brachiopod shell like a toenail, and the right spiral of an ammonite.

“What I actually love are hint fossils,” Graham stated. “They’ll inform you a lot.” Hint fossils are the stays not of the creature itself, however of its footprints, tracks, burrows or faeces. “Typically you’ll be able to see two tracks – perhaps two trilobites skittering throughout the sand – and you’ll see the place they be part of collectively for a bit, have a little bit social gathering. It’s simpler to consider previous landscapes once I can see traces of the creatures that lived in them. You suppose, wow, it was actually right here.”

Constructing on strategies pioneered by Smith within the early Nineteenth century, fashionable surveyors use fossils and microfossils to establish layers of chalk. Again in 2002, Farrant informed me, police known as on the assistance of native geologists when a tiny fragment of chalk was discovered beneath the wheel arch of the Soham assassin Ian Huntley. Two explicit microfossils had been found within the chalk: one discovered solely within the Seaford and one solely within the higher Newhaven. The presence of each microfossils meant that the chalk fragment may solely have come from a selected 2-metre thick layer – and the one place that chalk may have been pushed over was an area farm observe {that a} farmer had coated with that particular chalk, and the place Huntley claimed he had by no means been. The chalk fragment shaped a part of the proof that ultimately secured his conviction.

At the highest of the Beacon we sat down. It was very nonetheless and really silent. Someplace up above a skylark was calling. From right here you would see the fields of Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and Oxfordshire past. Within the distance a row of small bushes flamed yellow and pink, a line of fireplace alongside the sting of the inexperienced area. It made sense, I used to be considering, that the primary folks to dwell right here headed for this place, climbed up the hill to the place a view of the world opened out.

Graham ate a banana and stated that tomorrow she needed to attempt to gather sloes. “It’s not all the time as nice as this,” Farrant warned me. “You must come again when it’s a freezing, raining day in January and we’re caught surveying some industrial property in Watford.”

Chalk tracks on Ivinghoe Beacon in Buckinghamshire. {Photograph}: Robert Stainforth/Alamy

Chalk tracks on Ivinghoe Beacon in Buckinghamshire. {Photograph}: Robert Stainforth/Alamy

He obtained out a laptop computer and commenced to enter information. The map they had been engaged on is funded by the Environmental Company and two main water corporations. As a result of chalk is extremely permeable, it acts as an enormous aquifer, offering a supply of consuming water. The chalk additionally acts as a pure filter, purifying the water that drains by it. However there are additionally fractures within the rock – and right here the water flows as an alternative of drains. Water corporations must know the way the water flows by the chalk, the place it may be safely extracted. And for that they want an correct, detailed map of the totally different formations. The Holywell fractures differently from the Seaford. A crack within the Newhaven is just not the identical as one within the Zig Zag.

When he’d completed together with his laptop computer, Farrant pointed downhill. “Should you stood right here through the Anglian Glaciation you’ll have seen an ice sheet coming proper as much as the bottom of the chalk scarp there.”

The following chapter of the story of the formation of the Chilterns befell round 450,000 years in the past, when immense ice sheets coated the north of Britain, reaching down so far as Watford. Past the ice, the Chilterns was a wild expanse of chilly, empty tundra. Unable to permeate the frozen floor, melting water flowed over the floor of the land, forming river channels that ultimately lower down into the rock to create the dry valleys which are such a particular characteristic of the chalk panorama. “The entire of southern England has been superbly picked out by that periglacial weathering,” Farrant stated. Additional north, every thing was simply bulldozed by the ice. I pictured nice blocks of ice shifting remorselessly throughout a panorama – ice heavy sufficient to grind and clean away the very rocks in its path.

A few weeks after my journey to the Chilterns, I went for a stroll on the North Downs, on the opposite facet of London. Following a farm observe in the direction of the ridgeway, the thrill and roar of the M25 was faint however insistent, just like the distant rush of the ocean. Underfoot the trail was pale brown and, the place the skinny topsoil had blown away, vibrant white – the bones of the land uncovered. Reaching the ridge, I paused, turned and noticed London within the distance. Gray and silver towers developing out of a muzzy blueness away over the beech timber and red-tiled suburban roofs.

As I stood there, trying again in the direction of the town, it appeared as if the blueness intensified. After which it regarded for some time as if the outdated Cretaceous ocean had returned to the London basin. Or as if I used to be seeing a flooded metropolis a while sooner or later. I thought of melting ice sheets and sea degree rise and the way, as I stood there, the south-east of the island was sinking whereas Scotland rose up – a see-saw impact induced when the nice northern ice sheets started to soften round 20,000 years in the past.

After which, I imagined, the bottom within the metropolis would turn out to be heavy like a saturated sponge, the groundwater seeping up between the paving stones, effervescent up out of the drains and working alongside the gutters. The Thames would swell and over-top its banks. Fingers of brackish water creeping up Cheapside and into the grounds of St Paul’s. The water rising over the Homes of Parliament, Huge Ben, the Palace of Westminster. A blueness overtaking the panorama.

• Tailored from Notes From Deep Time: A Journey By way of Our Previous and Future Worlds by Helen Gordon, printed by Profile and accessible at guardianbookshop.com

• Comply with the Lengthy Learn on Twitter at @gdnlongread, signal as much as the lengthy learn weekly e-mail right here, and discover our podcasts right here