On this day in 1897, London’s first-ever road tunnel opened under the Thames, offering a connection across the river that East London had long been missing.

Although central London had plenty of bridges across the Thames, East London was poorly served and this was increasingly a problem with the growth of London’s docks and a population seemingly never stopping. There was a railway line running through Brunel’s Thames Tunnel, but apart from the slow Woolwich Ferry, there really wasn’t much in the way of road crossings in East London. By the 1880s this was becoming a serious problem, and finally, in 1887 plans were announced for two road tunnels and a pedestrian tunnel under the Thames at Blackwall.

The initial proposal, made by Sir Joseph Bazalgette, was commissioned by the Metropolitan Board of Works, but in 1889 the London County Council (LCC) took over the project and they scaled back the plans considerably.

Incidentally, although it’s a tunnel, the project was overseen by the LCC’s Bridges Committee, which is a minor but amusing point.

Anyway, the LCC scrapped plans for three tunnels, and came up with just one tunnel, this time designed by the LCC’s own in-house engineer, Mr Alexander Binnie. Construction was carried out by S. Pearson & Sons, starting in 1892. The total cost of the tunnel and associated roads came in at around £1 million, and as the tunnel was to be free to use, the cost of building it was funded by the LCC borrowing the money as debt.

It was to be a single road tunnel, with two lanes, and two pedestrian footpaths on either side. The tunnel was due to be completed by 1895, but suffered from a number of problems during construction, including two floods, and wasn’t eventually finished until May 1897.

Although the tunnel curves under the Thames and that’s often cited to stop horses bolting when they see the daylight, the reason is more practical. The approach roads couldn’t be on directly opposite sides of the river, so two roads lead down to the river tunnel, and it passes under the Thames at an angle to minimise the distance. Hence, the corners in the tunnel are the points where the river starts.

Construction was by a combination of cut-and-cover tunnels leading down to the river on either side of the Thames that then joined up with the tunnel dug under the river. To dig the river tunnel, three huge shafts were dug down on either side of the Thames. The shafts were dug down by building the huge shaft above ground, and then digging out the soil so that it would slowly sink under its own weight down to the depth needed.

They used a Greathead tunnelling shield to dig the tunnel itself.

To stop water flooding into the tunnel as they dug under the Thames, large airlocks were installed at the end of the tunnel, and the air inside pressurised. Working in the pressurised environment was known to be dangerous for the workers, so the wages were adjusted accordingly, with higher wages for higher pressures, and unusually for the time, they also set up a pension scheme for any who were injured during construction. However, six people died during construction, and it’s a measure of how dangerous construction work was at the time that it was lauded as a good thing that only six men had died during the works.

The tunnelling shield wasn’t like a modern tunnel boring machine, as this tunnel was dug by hand. The shield contained twelve compartments, and men would stand inside them digging away at the clay by hand, with the clay then removed by rail from behind them, and once enough soil was removed, the shield could be moved forward, and an iron ring installed behind to create the tunnel.

In the centre, the tunnel comes within six feet of the bottom of the river, so the river bed was padded with tons of puddled clay to prevent the river from bursting through into the tunnel below.

The main tunnelling work was completed in October 1896, but it was to require another six months to then fit out the inside of the tunnel with the glazed tiles, roadway and electric lighting before it could be opened to the public.

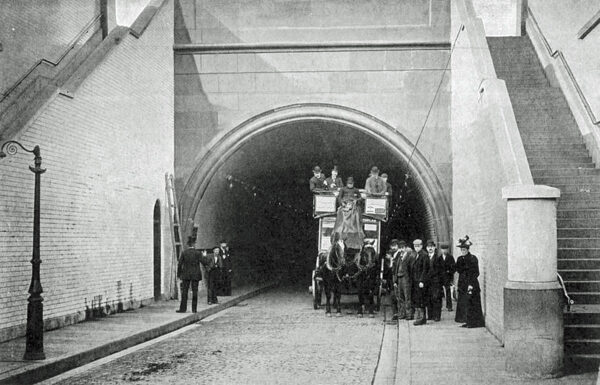

Some 10,000 official guests attended the opening, which took place 125 years ago today, in the afternoon of Saturday 22nd May 1897. Having 10,000 people attend an opening of a tunnel may seem a lot to us today, but back then, this was an engineering marvel of the world and it had gained a lot of attention during construction.

To give an idea of how much public interest there was, it was reported that it took at least three hours for people arriving at Maze Hill railway station to walk to the tunnel entrance so great were the crowds that had come to see the Royal procession and the tunnel open. Some people had a better view though, as they were employed by the company that owned two large gasometers in North Greenwich and they climbed up to sit on the metal frame to get a good vantage point. Perks of the job!

Having rode in carriages from central London, the opening by the Prince of Wales was by ceremonial golden key that unlocked the northern gates to the tunnel, and the Royal party then went through in horse and carriage to the south side where large tents had been erected for the reception.

The ceremonial opening completed, the tunnel didn’t open to the general public for another month though.

That was because the tunnel, already two years late was still unfinished as work on lining the inside with tiles was still not ready. The tunnel finally opened to the public, still needing tiling and some of the pedestrian stairs were not finished, at 10am on 24th June 1897. A plaque commemorating the ceremonial opening was added a few months later.

Such was the nature of the time, that the royal opening gained tons of news coverage, but the actual opening to the public was a mere footnote in many newspapers.

When it opened, buses advertised new routes taking people to the tunnel mouth, and then it was for people to walk through the tunnel to the other side, although a few tourist buses did run through the tunnel. Some 15,000 people were walking through the tunnel in the days after it opened, and a newspaper report that it was “extensively” used by cyclists.

Although there were complaints about noise, as the tunnel was lined with granite setts (cobbles) instead of using wooden setts, the tunnel was generally considered to be a huge success.

So much so that it wasn’t long before people were wanting more tunnels.

Other road tunnels under the Thames

Just over a decade after the Blackwall tunnel opened, the Rotherhithe tunnel opened, and in 1973, the Blackwall tunnel was doubled with the opening of a new tunnel next to it. The first Dartford Tunnel opened in 1963, followed by the second in 1980.

Coming soon, the Silvertown Tunnel next to the Blackwall is expected to open in 2025, and the Lower Thames Crossing is an awaiting-planning-consent road tunnel that may open in 2028.

When the Blackwall tunnel first opened, there were two narrow footpaths on either side of the road, but these were removed in the 1960s. One side was removed entirely so that the road could be widened, and the other side was blocked off and is used to carry fire safety systems. Today, only motorists are allowed down the Blackwall tunnel, although pedestrians can walk through the Rotherhithe tunnel if you’re mad enough to try it.

Wouldn’t it be fun to close the Blackwall tunnel say one evening and let the public walk through it?

Sources

The Sketch – Wednesday 16 January 1895

The Scotsman – Monday 24 May 1897

Huddersfield Chronicle – Thursday 15 October 1896

London Evening Standard – Saturday 13 April 1895

Morning Post – Monday 24 May 1897

Tower Hamlets Independent and East End Local Advertiser – Saturday 12 December 1896

Dundee Courier – Friday 25 June 1897

Pall Mall Gazette – Wednesday 11 March 1891

Globe – Monday 05 July 1897

https://www.ianvisits.co.uk/articles/todays-the-125th-anniversary-of-opening-the-blackwall-tunnel-54863/