The last time the Thames broke its banks and flooded central London was on 7 January 1928, when a storm sent record water levels up the tidal river, from Greenwich and Woolwich in the east as far as Hammersmith in the west. Built on flood plains, the capital was defended only by embankments. The flood waters burst over them into Whitehall and Westminster, and rushed through crowded slums. Fourteen died and thousands were left homeless.

After another catastrophic North Sea storm surge in 1953 caused floods along the east coast of England that were even more deadly – killing 307 people, including 59 at Canvey Island on the Thames estuary – discussion began about how to protect London.

Three decades later, the Thames Barrier was completed. A colossal engineering project, it spans 520 metres (17,000 ft) of river near Woolwich and has so far protected 1.4 million Londoners (and about £320bn worth of properties) from more than 100 tidal floods.

Q&A

What is The Rising Ocean series?

Show

It started slowly but is surely picking up speed: the ocean, long considered so big it couldn’t be affected by humanity, is creeping toward us. As the water warms and the ice sheets melt, sea level has risen more than half a foot in the last century – and even if we stopped producing greenhouse gases today, a very unlikely scenario, it will only keep coming. With 40% of the Earth’s population living in coastal zones, the UN has warned that the accelerating pace of sea level rise threatens a “mass exodus”.

What we do now matters. While stopping carbon emissions is the most important collective task, individuals around the world are fighting back against the rising waters in their own ingenious ways. As our islands vanish, our shorelines shrink and our cities flood, Guardian Seascape is telling the troubling but inspiring stories of how humanity is facing down The Rising Ocean.

Chris Michael, editor

Thank you for your feedback.

The ocean, however, is rising. With sea levels forecast to creep up by as much as a metre by 2100, and more extreme weather expected in a warming world, the Environment Agency (EA) says tidal defences upstream of the barrier must be raised by 2050 – 15 years earlier than expected. It cited “heightened risk of flooding” from rising sea levels.

Fourteen people died and thousands were made homeless in the 1928 Thames flood. Photograph: Alamy

Recently, the agency updated its plan to support the Thames Barrier and the wider tidal defence system, which incorporates eight other flood barriers, 200 miles of walls and embankments, and 400 other structures such as flood gates, outfalls and pumps. It expects the barrier to continue to protect London until 2070 – but that to protect the capital up to 2100, as planned, the structure may need to be replaced.

That decision – whether to build a new barrier or upgrade the existing one – will wait until 2040, with all options remaining open until then, it says.

Critics are concerned this timescale is too slow. In 2013-14, the barrier was closed a record-breaking 50 times. “We’re absolutely not ready,” says Prof Hannah Cloke, an environmental modeller and forecaster at the University of Reading. “Evidence shows sea levels rising faster than we thought and that storms like 2013-14 are more likely … We should be preparing for that and we’re not. The barrier was never designed to be closed 50 times a year.”

The Thames Barrier is a marvel of engineering. When open, its 20-metre- high gates lie flat, allowing water to flow freely through it and ships to pass. When there is a storm surge, hydraulic cylinders rotate the gates to create a solid wall of steel that prevents water from flowing upstream. Each of the 10 gates can hold back 9,000 tonnes of water.

But the barrier is ageing and the seas keep rising. “The Thames Barrier was designed at a time when sea level rise projections were far lower than projections today,” says Prof Jonathan Bamber, director of the Bristol Glaciology Centre. “Since then, sea level rise has been accelerating, and parts of London will be at risk if flood defences are not invested in very soon.”

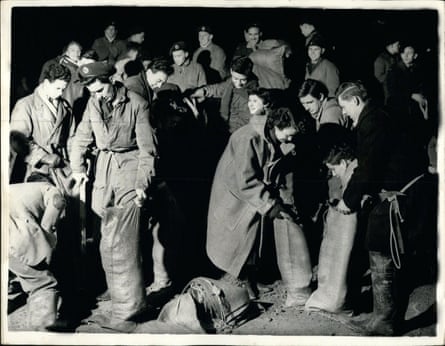

Students in Kingston-on-Thames fill sandbags at 2am on 2 February 1953 as the Thames bursts its banks. Photograph: Keystone Press/Alamy

Students in Kingston-on-Thames fill sandbags at 2am on 2 February 1953 as the Thames bursts its banks. Photograph: Keystone Press/Alamy

The EA acknowledges flooding will increase unless something is done – which it says the new plan addresses by including measures to reduce the strain on the barrier. The minister responsible for flood defences, Rebecca Pow, described the Thames Estuary 2100 plan as a “world-leading climate adaptation strategy”.

But the EA’s own guidance also says the barrier should not be closed more than 50 times a year. If 50 becomes the norm, it says, the barrier could fail. The barrier was closed four times in the 1980s, 35 times in the 1990s, 75 times in the 2000s and 74 times in the 2010s.

Bar chart showing closures of Thames Barrier since 1982

The cost of future-proofing in the 2100 plan is estimated to be £16bn – a figure that has increased by 50% since 2012 as defences have deteriorated faster than expected. But the EA has acknowledged the main form of government investment, the flood defence grant-in-aid, will not be enough. Where the additional money will come from, it has not said.

A data analyst and modeller who contributed to the Thames Estuary 2100 review expressed confidence in the agency’s plan, arguing it takes into account the risks posed by the rising oceans, as well as maintenance issues. “It recognises if sea level rise is smaller than expected, it can raise defences,” says Prof Ivan Haigh of the University of Southampton.

However, he added: “If [the] rise is larger, we will need a new barrier – and not just a barrier, but a barrage. If it is over 2 metres, we will need a dam. We could protect London up to about 5 metres of sea level rise if we built a barrage.”

The main threat to the barrier is not that it will be overrun by water, but that opening and closing it repeatedly makes it harder to keep it in good condition. “Once you start to close it so many times a year, you don’t have time to do maintenance,” Haigh says. “With 1 metre of sea level rise, you could go from 10 closures a year to many hundreds of closures a year – perhaps up to 300.”

If you continue to close it for fluvial closures, then the barrier will come to the end of its life by 2030 or 2035Ivan Haigh, University of Southhampton

About half of the 207 closures to date have been not to stop tidal floods – the barrier’s main function – but to alleviate fluvial flooding, when water overflows on to the surrounding land due to excess rainfall. To reduce the need to close the barrier, the EA plans to stop using it for fluvial flooding events in west London, including Richmond and Twickenham, by 2035. It is also working to improve the accuracy of its forecasts.

“If you continue to close it for fluvial closures, then the barrier will come to the end of its life by 2030 or 2035,” says Haigh. “They plan to reduce the number of closures by half and reduce forecasting error. If they can do these two things, they can keep the number of closures below 50 a year.

“If they stop the fluvial closures, reduce forecasting error and at some point raise the defences in London, I’m fairly confident they can keep the barrier until 2050 or 2060.”

The barrier is now being used up to 50 times a year – far more than was intended. Photograph: Jill Mead/The Guardian

The barrier is now being used up to 50 times a year – far more than was intended. Photograph: Jill Mead/The Guardian

An EA spokesperson says the Thames Estuary 2100 plan “takes account of a range of possible climate futures”. They say the agency has used the “higher scenario” of sea level rise from the UK’s official climate projections from 2018.

The spokesperson says: “We are committed to reappraising our options ahead of the next review in 2030 and this may result in some being removed if they are no longer economically or technically viable. A final decision will be taken by 2040 to ensure that an upgraded or new Thames Barrier can be built and operational in time for 2070.”

Cloke sees the timescale differently, noting that it took 31 years to build the barrier after the 1953 flood. “This wait-and-see attitude, it’s a bit like building a house and not putting a roof on it to wait and see if it rains,” she says. “We could do something about it now. It’s so shortsighted.”

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jun/30/before-the-flood-how-much-longer-will-the-thames-barrier-protect-london