When he was aged six, Sam Webb accompanied his father to the grounds of the Tate gallery in London, to see an exhibition of prototype factory-built homes that gleamed with promise for better postwar social housing. That show, in 1943, resonated with him: three years earlier, during the blitz, he had seen the windows of his family’s house and shop in East Finchley, north London, blown away. It was a place with an outside toilet and gas lights that he described as “Dickensian”.

“Stepping into an Arcon Mark V prefab was like stepping into a future I could only dream of,” he recalled. “Here was a house so beautifully designed, it had everything.”

Webb, who has died aged 85, went on to become an architect himself. However, he spent most of his career warning about the darker reality of Britain’s council housing rebuild, when tower blocks sprang up across bomb-damaged cities. It was to become a vocation underpinned by his empathy for tenants and disappointment at a lost opportunity to create a new generation of truly decent housing.

As a just-qualified local authority architect, Webb was already concerned about the lethal risks of prefabricated high rises when, in 1968, Ronan Point in Newham, east London, suffered a partial progressive collapse in which four people died.

Ronan Point tower block, 15 June 1968. Photograph: David Graves/Rex/Shutterstock

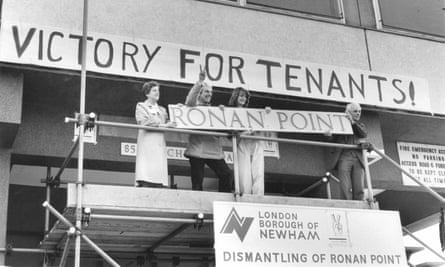

Later, after tenants were rehoused in the fixed-up block, his practical research and grassroots campaigning led to it and eight similar blocks being evacuated and demolished in 1986. He was an expert adviser to the victims of the 2009 Lakanal House fire that killed six people in Southwark, south London, and most recently gave evidence in the public inquiry into the disaster that overtook Grenfell Tower, north Kensington – the causes of which have several alarming parallels with Lakanal and Ronan Point.

Webb was a gentle, practical man focused on people rather than buildings, not common in an architectural community dominated by strong egos and high-concept designs. But he was politically sharp, dogged in his campaigning and had an eye for publicity and causing the right kind of trouble. He worked with the investigative journalist Paul Foot at Private Eye on articles that exposed not just the safety scandal of the large-panel systems used at Ronan Point, but led to the uncovering of the corruption scandal involving the architect John Poulson that led to the resignation of the home secretary Reginald Maudling in 1972. And in 1970 he helped the director Joan Littlewood stage The Projector, a musical set in Restoration London but about Ronan Point, at the nearby Theatre Royal, Stratford. He also advised the TV director Adam Curtis for his 1984 documentary The Great British Housing Disaster.

The key period of Webb’s career began in 1983 when he was a senior lecturer in construction and design at the Canterbury College of Art and School of Architecture. While at a national tower blocks conference, he listened carefully to tenants in the now reoccupied Ronan Point who could smell the dinner being cooked 20 floors beneath them and hear conversations far below.

“The one thing that’s different about Sam Webb was that when the tenants said: ‘We have a problem, Sam, come and have a look,’ he came,” said Sue McDowell, chair of the Newham Tower Block Tenants Campaign. “He didn’t think ‘Silly tenants, you don’t know what you’re talking about.’”

Webb and his students found gaps between the walls and floors wide enough to drop strips of paper down. He took a term off from his teaching duties to investigate and his surveys were enough to trigger the council landlord to evacuate the block for a second time.

“That term was like a breath of fresh air because I wasn’t surrounded by architects,” he recalled. “I had to talk to people and explain quite complex things in a way they could understand – not just tenants, TV interviewers and reporters.”

‘They were not seen as places to live in, they were seen as production exercises to make money,’ he said of high-rise housing

Webb insisted it should be dismantled rather than dedestroyed without further examination, to find out more about what was wrong. One story in particular gained media traction: on dismantlement, it emerged that a load-bearing joint had been stuffed with an old copy of the Daily Mirror.

“They were not seen as places to live in, they were seen as production exercises to make money,” he said of high-rise housing in 1988. “I think in 20, 25 years time, maybe sooner, that bubble will burst and all sorts of problems will arise.” Thirty years later he saw that bubble burst with the scandal that followed the Grenfell Tower fire, in which tens of thousands of leaseholders have found their homes unsaleable because of safety fears.

Webb’s judgment came to be widely trusted. When he spoke to the Guardian just hours after the Grenfell fire, he identified the problem of “wrapping postwar high-rise buildings in highly flammable materials and leaving them without sprinkler systems”.

“I really don’t think the building industry understands how fire behaves in buildings and how dangerous it can be,” he said. “The government’s mania for deregulation means our current safety standards just aren’t good enough.”

He had nailed two of the key contributors to the deaths of 72 people that the public inquiry has spent much of the last five years teasing out.

Born in Finchley, Sam was the son of Marie Watkins, a dressmaker, and her husband Samuel Webb, a licensed victualler. They ran a shop whose customers included the family of Peter Sellers. From Christ’s college, Finchley, Sam went to the Northern Polytechnic, now part of the London Metropolitan University, where his architecture degree course was interrupted by two years’ national service in the RAF based in Stornoway, on Lewis in the Outer Hebrides.

In 1961, he married Sylvia Bartlett, whom he met while studying, and after qualifying in 1965 he worked on housing design at the London Borough of Camden, while also teaching at architecture schools including the Architectural Association and Cambridge. He travelled to Maoist China in 1973.

The start of the operation to dismantle and study the 22-storey building, May 1986. Photograph: Garry Weaser/The Guardian

The start of the operation to dismantle and study the 22-storey building, May 1986. Photograph: Garry Weaser/The Guardian

In 1970, after the Ronan Point public inquiry, he spent three and a half weeks in the ministry of housing, ploughing through all the files, and emerged convinced of a wider problem. He went to parliament to meet MPs led by the Labour politician Tom Driberg and gave them a dossier. One MP, whom he did not name, said: “If he repeats this outside parliament he will be sent to prison for criminal libel.”

“I was talking about people’s lives,” Webb said.

His first marriage having ended in divorce, in 1974 he married Sheila Crichton. They had three daughters, Rachel, Hannah and Sarah, and the relationship lasted until 2008. In 1975 he took a job lecturing in construction and design at Canterbury and remained in academia until retirement in 1996. He later moved to Cambridge to be near his family. After Grenfell, he worked 12-hour days to assist anyone who needed help.

In 2021 he was appointed MBE for services to architecture. His citation read: “Never afraid to ask difficult questions of those in authority, he made a unique and expert contribution … and has probably saved many lives in so doing.”

He is survived by his daughters and six grandchildren.

Sam (Samuel) Webb, architect and safety campaigner, born 5 August 1937; died 24 September 2022

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/oct/04/sam-webb-obituary