The torrent of sewage that poured into Tommy Stadlen’s west London home left his pregnant wife waist high in a sea of grey-brown liquid, dead rats washing into his neighbour’s flat — and a strong conviction that the water bills he had paid for 15 years had not quite delivered the quality of service expected.

The immediate cause of the flooding, which closed roads, underground stations and shops in the British capital in July, was a fierce downpour that delivered a month’s rain in 90 minutes.

But while extreme weather, rising population density and unconstrained building contributed to the toxic flooding, it was also the result of decades of under-investment in the nation’s water infrastructure.

“This is the richest borough, in one of the world’s wealthiest countries and yet it lacks a functioning sewage system,” Stadlen, a technology entrepreneur, told a packed Kensington town hall attended by Thames Water and many other frustrated local residents in September.

While public anger towards water companies has been bubbling for years, it has erupted in the past few months, as unknown quantities of raw sewage and storm water have repeatedly been poured into Britain’s rivers and seas, increasing pressure on the government and regulators to act.

The industry is now facing its biggest wave of protests since it was privatised more than 30 years ago, as campaigners, from the Windrush Against Sewage group in Oxfordshire to Ilkley Clean River in Yorkshire, try to force action from companies and policymakers.

Their efforts have gained support and publicity from celebrities including Feargal Sharkey, whose Twitter campaign helped secure a vote in parliament for action against sewage pollution, and Bob Geldof, who has urged people near his home in a town on the Kent coast to stop paying their water bills.

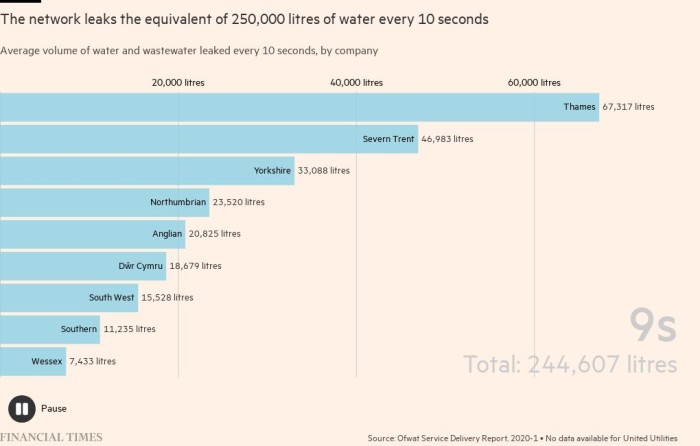

The biggest focus for campaigners has been storm overflows — the 15,000 pipes that discharge sewage into rivers and seas when it rains.

Despite the unpalatable consequences for swimmers and wildlife, a certain amount of this dumping is allowed under Environment Agency rules. But until recently most pipes were not monitored and water companies were responsible for reporting their own breaches. The environmental watchdog has launched an investigation into whether companies have been exceeding legal limits.

The new Environment Act requires water and sewage companies to reduce overflows, but there is no set timetable or quantifiable targets. The government is required to publish a new plan to reduce overflows by September 2022.

But if the pressure for change is there, the cash is not. This month, industry regulator, Ofwat, warned that at least two providers — Southern Water and Yorkshire Water — were in such poor financial health in March that there were concerns over their ability to deliver environmental improvements. Yorkshire Water said its “financial structures are robust and resilient.” Southern has since been taken over by the Australian infrastructure manager Macquarie.

Investment fell as dividends flowed

The privatisation of England and Wales’ regional water suppliers 30 years ago came with a promise that investors would deliver much needed upgrades to the nations’ sagging water network.

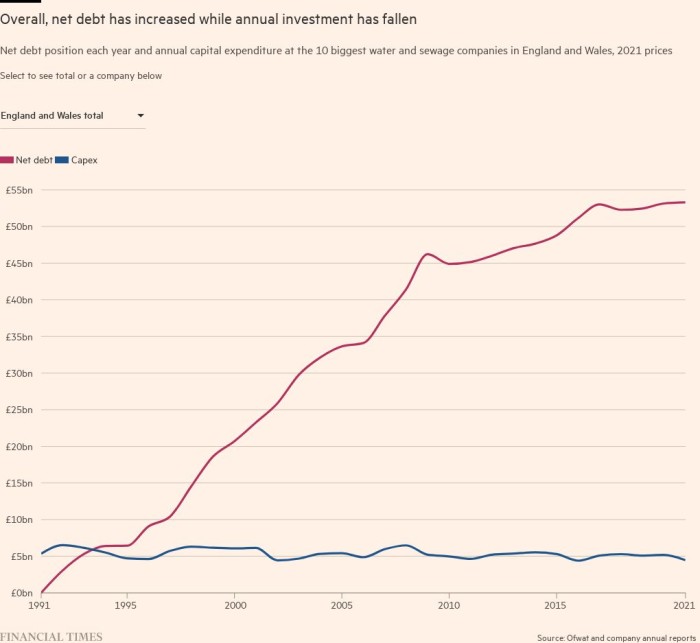

Although there was an initial rise in spending, as some companies sought to meet European water quality directives, research by the Financial Times showed that total capital expenditure by the 10 biggest water and sewage monopolies had declined by 15 per cent since the 1990s — from £5.7bn to £4.8bn a year.

One exception is Thames Water, which has increased expenditure, although not by enough to stop leaks and burst pipes.

Over the same time the companies — which were sold off with no debt and handed £1.5bn — have borrowed £53bn, the equivalent of around £2,000 per household. Much of that has been used not for new investment but to pay £72bn in dividends.

“The purpose of private water companies has indeed been to profit-maximise,” said Dieter Helm, a utilities expert at Oxford university.

Ageing pipes soak up investment

The concern now is that with high debts to service and ageing infrastructure to maintain, water companies have little financial headroom to improve their Victorian era pipes, even though customers’ bills have risen by almost a third since 1991.

One water industry executive said companies were spending more on “maintaining deteriorating assets than replacing them.” He pointed to the use of water jets to deal with blockages as an example. “These are a poor substitute for improving the wastewater network, and will hasten pipe deterioration,” he said.

Olivia Jensen, a lead scientist at the National University of Singapore, said that in Singapore the government department responsible has an active management plan including leak detection systems. “This is very different from England, where the emphasis has been on squeezing more out of the existing system rather than building a system that will function well in the future,” she said.

Ofwat, which sets limits on how much water companies can raise from bills to invest, said overall expenditure including maintenance had increased by 42 per cent, from £3.9bn to £5.6bn per year since the 1990s. It said some spending, such as on sustainable drainage systems, would not have been included in the overall capital expenditure figures.

There has also been some improvement in transparency around sewage spills, with new electronic monitoring devices being fixed to pipes. Water companies will be required to publish storm overflows within an hour of them happening, which does not reduce pollution but at least helps to protect public health by providing warnings.

But this still does not solve the problem of how to pay for infrastructure upgrades to cut sewage outflows.

A recent government commissioned report estimated the cost of eliminating storm overflows at between £350bn and £600bn — an unrealistic sum for the companies to pay that could add up to almost £1,000 to customers’ annual bills.

Even more minor improvements — such as reducing spills in “sensitive catchments” by three quarters — would likely cost at least £18bn, the report said.

However many companies believe they will be able to make substantial improvements for less.

Southern Water, which received a £1bn emergency equity injection from Macquarie in August, a month after the company was hit with a record £90m fine for dumping billions of litres of raw sewage into rivers and seas, has pledged to halve pollution incidents by 2024 compared with 2019, while ensuring bills do not rise by more than inflation.

It estimates the cost of replacing its total sewage network at a crippling £50bn — but will complete significant upgrades to its existing infrastructure, half of which was built before the 1970s, at a cost of £2bn.

The industry body, Water UK, said it was “pushing the government to encourage Ofwat to authorise schemes that meet . . . environment targets, including ending all ecological harm from overflows, ensuring resilient water supplies, and meeting our ambitious 2030 net zero target.”

But Ofwat said companies “need to focus on improving their performance before asking for more money from customers”. “Water companies have substantial money to invest, with a £50bn package agreed . . . for the next five years”.

Helm argued it was “implausible” that the regulator could allow companies to raise prices high enough to pay for the extent of the upgrades required during the next regulatory period, especially when customers are struggling with inflation and interest rate increases. He said wider reform of the regulatory system was needed. Others such as We Own It, a campaign group, are calling for renationalisation.

Back in Kensington, Stadlen has pledged to keep fighting on behalf of the flooded residents. “We will not allow incompetent bureaucrats and cost-cutting private companies to fail them,” he told the September meeting.

https://www.ft.com/content/b2314ae0-9e17-425d-8e3f-066270388331