At the Dugdale Centre in north London, where a theatre has been hastily converted into a coronavirus vaccination site, 72-year-old John Blake is rapidly revising his low opinion of the government’s pandemic response.

Having braved a bout of snow in the capital to receive his inoculation — one of the few authorised reasons for breaking England’s strict stay-at-home rules — he said ministers seemed to “have got a grip on things” and believed the vaccination rollout marked a turning point.

“This is all part of the journey towards lifting the lockdown,” he reflected after his jab. “I feel like we’re contributing to getting out of this situation.”

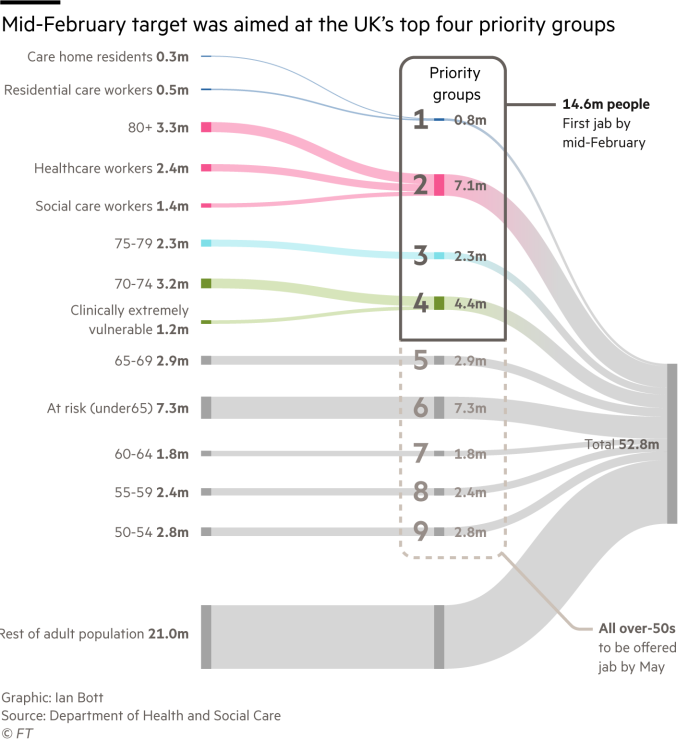

The UK had carried out more than 14m vaccinations by Friday morning and was fast approaching the target of inoculating the 14.6m most at risk from Covid-19 by the start of next week. Only Israel and the United Arab Emirates, among larger countries, have inoculated more per head of the population.

Global leadership is an unaccustomed status for a country with one of the highest rates of excess deaths in western Europe. Multiple missteps, such as the government’s failure to deliver on a “world beating” test and trace system, have engendered cynicism about its handling of the pandemic.

The UK’s achievements have come despite far more constrained vaccine supply than Israel, for example. This has ruled out a demand-led model in favour of a “risk pyramid” laid down by government advisers, with the oldest immunised first alongside frontline health workers.

Jeremy Hunt, UK health secretary until 2018, said Asia had provided inspiration. Having failed to learn from that region’s recent experience in tackling deadly diseases caused by other coronaviruses in the early part of the pandemic — the UK halted community contact tracing, for example — the opposite was true when it came to vaccination.

“The main difference is that we really did learn the lessons from Sars and Mers when it came to the importance of the vaccine,” he said.

The Financial Times has spoken to more than a dozen people at the heart of the programme to discover the key decisions that were taken and examine whether the right lessons were learned from a litany of earlier failures.

Planning began long before it was clear whether any of the vaccines being developed at historic speed would win the approval of regulators. Back in the summer UK prime minister Boris Johnson put Sir Simon Stevens, head of the NHS in England, in charge of delivering the country’s biggest ever mass inoculation campaign.

The challenge was to avoid the problems that had befallen the highly centralised test and trace system, which had largely ignored expertise on the ground.

Stevens chose a different approach. Rather than creating a new system, he used existing groups of GPs, known as primary care networks (PCNs), which each cover up to 50,000 patients, as his main conduit. Each had to commit to vaccinating for 12 hours a day, seven days a week.

In total, around 1,500 vaccination centres have been established in England, including some in football stadiums and other large venues, staffed by 30,000 NHS workers and as many as 100,000 volunteers.

Some decisions were devolved — PCNs chose their own jabbing sites, for example — but for others the NHS’s ability to compel action through national edict proved effective.

When, several weeks into the rollout, ministers took the key decision, announced on December 30, to delay second doses to stretch supplies, Stevens, along with UK chief medical adviser Chris Whitty held a video call with hundreds of PCN leaders on a Sunday night to explain the new policy. The next week, second shots largely stopped — a level of compliance a more fragmented health system would have struggled to secure.

Planning had moved into a higher gear in November. With regulatory approvals for at least one vaccine imminent, Emily Lawson, NHS chief commercial officer, selected by Stevens to run the programme, assembled military and private sector support.

Brigadier Phil Prosser, commander of the army’s 101 Logistic Brigade, was taking part in an exercise with more than 2,000 soldiers on Salisbury Plain when he got the call on November 11 instructing him to leave immediately to start work on vaccine delivery.

Five days later, he and 50 military logistics experts were installed at the NHS headquarters in Skipton House, south London, to help co-ordinate distribution and set up vaccination centres.

Military specialists calculated the optimum location of centres to ensure every UK resident could access a jab within 10 miles of home, as ministers had promised. Security officials worked out how to safeguard shipments of vaccines from theft or attempts to disrupt the rollout.

The NHS has drawn on the logistics strength of the military to make the vaccination programme a success © Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images

“There’s no other supply chain that’s built like this,” said Prosser. “This is the largest vaccination programme this country has ever run.”

Three weeks later, on December 8, the first cohort were inoculated.

For those at the sharp end, the day starts at 8am with a meeting chaired by Lawson, where the head of each delivery group — GPs, hospitals and mass vaccination centres — reports on progress and the logistics team briefs colleagues on vaccine stocks for the next three days.

Palantir, the US data analytics company which had also worked with Lawson previously on a mechanism for PPE delivery, was contracted in November to provide a vaccine supply database.

“The issue essentially is how do you get it into the right arm in the right place,” said Louis Mosley, head of Palantir UK, who works on the programme. “You’ve got a huge number of logistical constraints, because the vaccine expires . . . [and] you often don’t know until the last minute how much you’re going to get.”

Each vaccine centre set up outside GP practices or hospitals needs more than 400 items of equipment to function, from needles to fridges and resuscitation equipment. Palantir’s system brings together warehouse inventories and information about patients and the readiness of trained staff. The database also keeps a running total of vaccinations to give the NHS instant progress reports. Palantir said it does not receive or hold identifiable patient data.

When it came to allocating the vaccine, the uniting principle has been to ensure equal access. Christina Pagel, professor of operational research at University College London, said that in Germany, by contrast, it is usually up to individuals to book an appointment once they are informed they are eligible. She said that sort of approach favoured the “tech-savvy” and made the process a “bit of a lottery”.

The vaccination programme has focused on the elderly, the clinically vulnerable and health and social care workers © Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg

However, the scale of progress, and the political narrative ministers have woven around it, would by now look very different were it not for the decision to delay the second dose of the UK’s two approved vaccines by up to three months.

Supplies of the vaccine stood at only half the volume needed to fully immunise the most vulnerable by mid-February, threatening to leave millions unprotected as troubling new variants spread.

That move sparked international criticism, including from Anthony Fauci, the US president’s chief Covid-19 adviser. This week, however, the World Health Organization backed the approach with the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine — one of the two used in the UK.

Mary Ramsay, head of immunisation at Public Health England, said the agency had originally discussed the importance of aligning the dosing intervals for the BioNTech/Pfizer and Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines, which were meant to be given respectively three and four weeks apart. “Operationally it was felt it would be easier to stick to a single interval,” she said.

Then data came in from AstraZeneca showing the effectiveness of a single dose up to 12 weeks. Moreover, as more analysis came in from the Pfizer trials, following the vaccine’s approval by regulators in early December, it reassured government advisers that it, too, was likely to be highly effective after the first dose — although the US pharma group was insistent on sticking to the approved three week schedule.

Former UK prime minister Tony Blair, who was an early advocate of the delayed second dose strategy, praised the government for the rollout of the programme. “I was sceptical as to whether the government would perform the logistics effectively enough but . . . by and large, they have.”

Covid-19 vaccines being flown to the Isles of Scilly © Hugh Hastings/Getty Images

While the numbers vaccinated point to a successful project, there have been inevitable bumps along the road. Some GPs have criticised the model through which vaccine supplies were “pushed” out to them, particularly those with low-income patients who tend to suffer poor health at younger ages.

One GP told the FT of giving doses of the Pfizer vaccine to private dentists from far outside their area, to avoid wasting supplies, because the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation rules said it must go to frontline healthcare workers or over-80s — and few lived beyond that age in their practice. (The rules do allow early vaccination of younger people deemed to be “clinically extremely vulnerable”.)

Blair said the UK must now come to terms with the idea of vaccine distribution as a constant and recurring challenge with new variants threatening to defeat the first generation of jabs. “You have got to stop thinking about this as a crisis, with a beginning and an end, and look at it as a new state of the world.”