Thomas Tuchel’s unbeaten start as Chelsea boss has undoubtedly been a positive one. But slight concerns about the midfield make-up after the 0-0 draw with Wolves led to further murmurs of discontent after a shaky spell against Spurs and an unconvincing win over Sheffield United.

The much-maligned pairing of Jorginho and Mateo Kovacic has once again faced heavy criticism, with Jorginho withering under Sheffield United’s intense pressing and marking and Kovacic failing to deliver in crucial attacking areas.

Tuchel has a challenge on his hands in finding an effective solution to the midfield conundrum. What could this mean for the returning N’Golo Kante? Where does Billy Gilmour, who the club considered loaning out in the January window, find himself in the grand scheme of things?

West London Sport looks at why the “Jovacic” partnership has proved problematic, and how a change in midfield could be on the cards soon.

Losing control?

Chelsea’s numbers against Wolves and Burnley made for great reading. The Blues starved the opposition of the ball with 78% and 71% of possession respectively, allowing zero shots on target. Wolves’ dangerous counter-attacking threats and Burnley’s robust physicality were both neutralised effectively.

The first signs of trouble arrived in the second half against Spurs, where Jose Mourinho’s side managed 53% of the ball and five shots (as many as Wolves and Burnley combined.) A spirited Sheffield United suffocated Jorginho, who lost the ball 14 times – more than in any of his other games under Tuchel.

Ben Chilwell conceded a penalty but was saved by the offside flag, while Antonio Rudiger scored a calamitous own goal. Tuchel’s previous sides blew teams out of the water with devastating attacks, while preferring to defend by pressing with quick and high intensity.

Why, then, are slower players like Giroud, Alonso and Jorginho starting, when dynamic players such as Abraham and Chilwell are on the bench?

Caution not misadventure

Tuchel’s early approach at Chelsea has been one of caution, with the focus on stemming the steady slide from first early in the season to 10th before the Wolves game. Against Wolves, Tuchel himself said he opted for experience, with most of the fit senior players – Giroud, Cesar Azpilicueta, Thiago Silva, Alonso, Rudiger and Jorginho all playing (at least four of those six have featured in every game since).

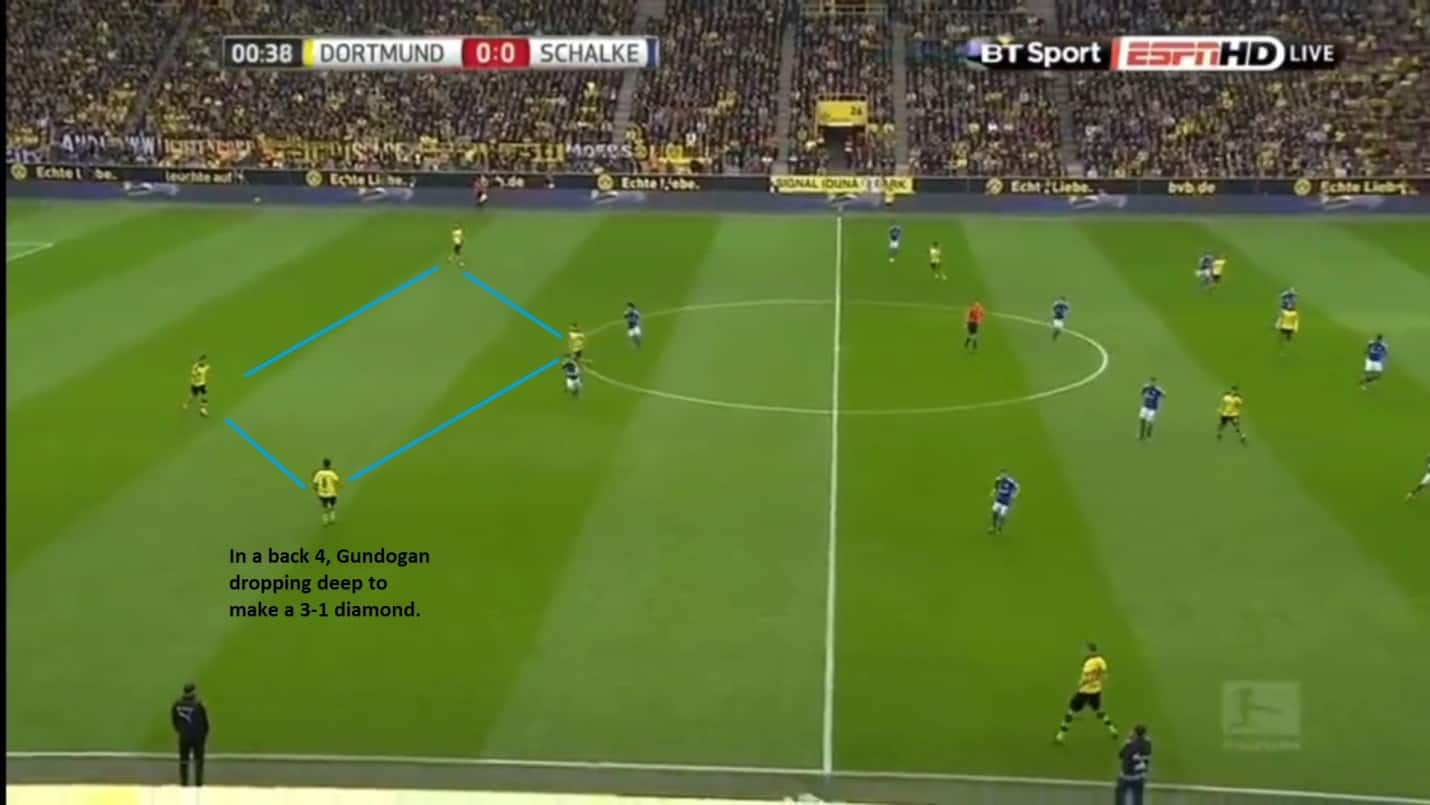

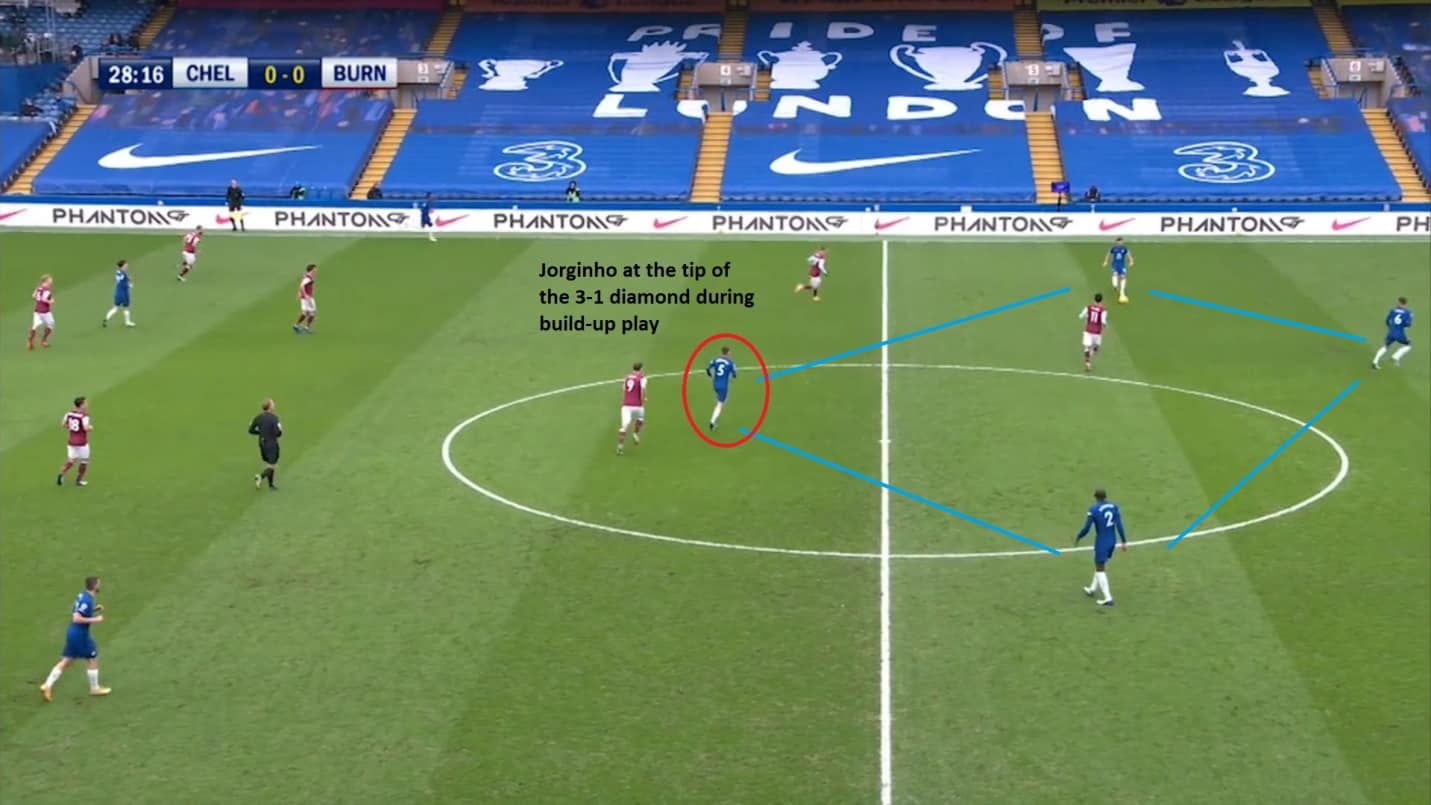

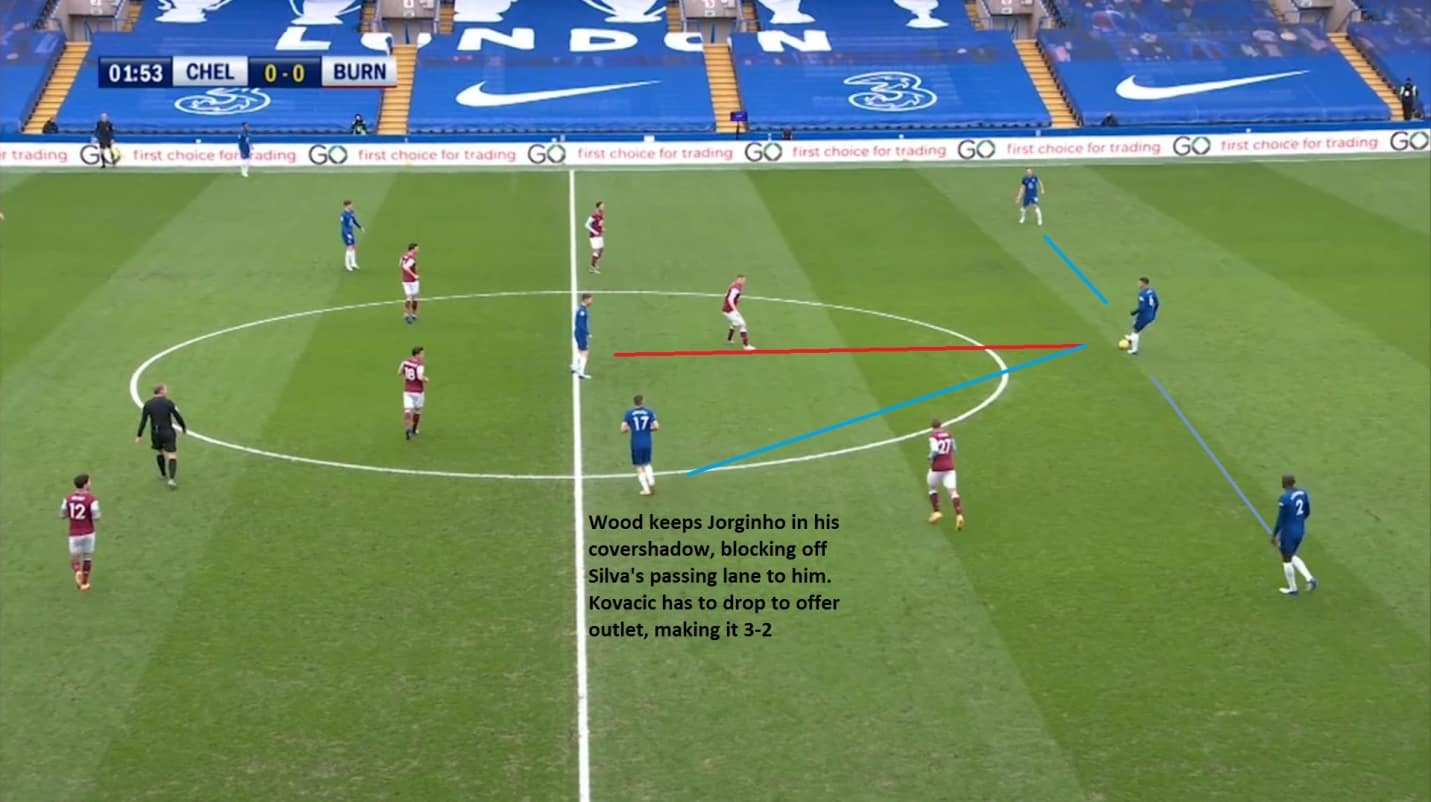

The watchful approach has also taken root in Tuchel’s tactics, where he has abandoned his favoured, bold 3-1 build-up shape (three centre-backs, one defensive midfielder) which he used at Dortmund and PSG, for a safer 3-1/3-2 hybrid (three centre-backs, two DMs).

This could also be because at both his previous sides, Tuchel had a player who possessed all the qualities he demands in a lone DM – mobility, positional intelligence, ability to cope with high-level pressing, high work-rate and the talent to move the ball forward quickly.

At Chelsea, no single player embodies all those abilities, leading to Tuchel dividing responsibilities between Jorginho and Kovacic, something that is starting to cost Chelsea in attacking phases of play. With Chelsea now up to fifth, Tuchel could be tempted to experiment.

A 3-1 or a 3-2?

So what is the issue with a 3-2 shape instead of a 3-1?

The first problem is that two players – Kovacic and Jorginho – are performing a duty that was ideally reserved for one at Dortmund (Julian Weigl/Nuri Sahin) and PSG (Marco Verratti.) With five players in defensive phases and Mount occupying a free role between lines, this leaves only four attackers against the opposition’s four defenders, a comfortable situation for most defences.

At Dortmund and PSG, the 3-1 allowed Tuchel to have five, sometimes six, attackers against a back four, providing superiority in terms of quality and quantity.

At Chelsea, Kovacic has played well in defensive phases and transitions, dropping deep when Jorginho has required support and using his speed to track runners and dribblers. Kovacic is also great at swift attacking transitions, often moving the ball quickly and breaking lines with his fantastic ball-carrying skills. It is in the final third that the Croatian has been poor; his final pass lacks timing, imagination and/or purpose, while his shooting is astonishingly wayward and inconsistent for a player of his quality.

This isn’t Kovacic’s fault. There wasn’t as much onus on Tuchel’s previous DMs to create scoring opportunities. At Dortmund, that responsibility fell on the shoulders of more creative players like Shinji Kagawa, Ilkay Gundogan, Ousmane Dembele, Gonzalo Castro, Christian Pulisic and Henrik Mkhitaryan, while at PSG, six out of Di Maria, Neymar, Johan Bernat, Thomas Meunier, Icardi/Cavani, Sarabia, Draxler and Mbappe provided potent firepower, even while playing a back four.

Tuchel’s biggest headache now is whether to persist with a midfield that has conceded only once in five games but only scored five, or to revert to a more attacking line-up that will add more pressure on the defence, but will be more clinical in attack.

© Chelsea TV

© Chelsea TV

© Chelsea TV

© Chelsea TV

© Chelsea TV

© Chelsea TV

© Chelsea TV

© Chelsea TV

Solving the midfield conundrum

There are multiple ways Tuchel can choose to solve this midfield dilemma, but none of them are straightforward.

Each involves dissolving the “Jovacic” partnership, and reverting to a 3-1, with the extra slot going to one of many exciting options on the bench (or still injured ones), like Kai Havertz, Hakim Ziyech or Pulisic (who thrived in a similar role under Tuchel at Dortmund).

The first is benching Jorginho, and converting Kovacic into the lone DM. Kovacic is excellent at escaping pressure, highly mobile, has been moving the ball quicker under Tuchel and is a tireless, selfless workhorse.The major downside is that in the past he has struggled in the lone pivot role, often lacking composure in his build-up play. The lone DM role will also demand more positional discipline, meaning he has to either greatly reduce his tendency to dribble, or eliminate it altogether in a bid to better protect the back three.

The second could see N’Golo Kante come in at DM meaning one or both of Kovacic and Jorginho drop out, something Frank Lampard often resorted to in his 4-3-3. Tuchel has said he sees Kante playing in one of the two “double six” roles. But the Frenchman’s world-class anticipation of danger, ability to inflict claustrophobia-inducing pressure and his high volume of defensive work makes him an ideal candidate. The downside is that Kante passing under pressure hardly inspires confidence, and he is severely limited in a lone pivot where he isn’t free to rely on his terrific instincts and intelligence, and has to resort to reacting to danger rather than acting to prevent it altogether.

The third option, the most overlooked of all, could be the most effective. In 19-year-old Billy Gilmour, Tuchel possesses a player in Verratti’s image, and with the promise Weigl displayed before he was trusted to become Dortmund’s fulcrum. Gilmour (1.7m) is actually taller than Verratti (1.65m) and has all the ingredients to become a similar giant in midfield.

Tuchel himself revealed his admiration for Gilmour in one of his first interviews as Chelsea boss, stating that he “is a very strategic guy. A very high level of game understanding. Very good in the first contact. He is super-quick, super-fast with his feet. Super-fast with his decision-making and very, very good in positioning.”

When he bossed two strong midfields from Merseyside in a week and earned two man-of-the-match awards, Gilmour played at the base of the midfield and shone in the role, effortlessly evading pressure, anticipating danger and moving the ball quicker than Jorginho.

Against Everton, he also ran 12.62 kms, underlying his capacity for putting in the hard yards to complement his technical brilliance. Tuchel did raise doubts on Gilmour’s ability to “compete in the centre of the field in the most physical league in the world”.

But there’s a view that power resides where people believe it resides. It’s a trick. A shadow on the wall. And a very small man can cast a very large shadow. The teenage Scot could yet be the key to unlocking Tuchel-ball’s full potential.